Comparative Possibilisms In the Form of Historiography

Matter is a tendency toward spatialization.

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter

Setting up Space for Historiography

In questioning how to do historiographic work, the emphasis of do encapsulates and conflates method/ology, subject matter, and evidence all into a single word. Debates on how to do historiographic work raise as matter of concern who or what is being researched, how the text is being written (through what lens is the history being seen), and what the history contributes to knowledge in the discipline of rhetoric. The histories of rhetoric could fill volumes of text categorized by time, subject/object, method, methodology. Histories invoke other histories as acts of carrying forward, of pausing, or even revising, but this relationality of texts is based on events in time. While methods of historiography continue to work towards attention to the agency of objects and space on an event (a shift in perspective from human to nonhuman) and to look at events as more ecological in composition (made up of many elements), the form these histories take, the space they occupy, is bound by lines in time.

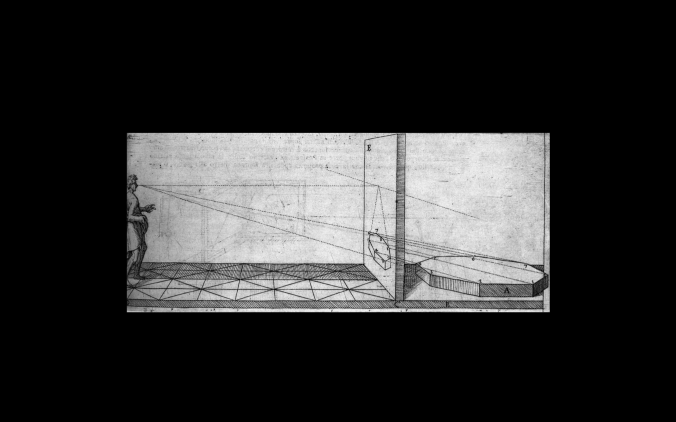

Rhetorical texts occupy rectangular fields in books and journals, with the occasional rupture of this rectangular frame in digital publication environments. I am curious what historiographical texts might be able to take as matter of concern if they are able to matter, to occupy spatiality. Writer William Burroughs developed a concept of media being, that he described as an individual who mixes and is mixed, who composes with media by commutating, appropriating, visualizing, and chorally structuring knowledge. The concept of chora, credited to Plato, designates a receptacle, a space, or an interval; the space creates time and place conditions. In “Toward a Post-Techne Or, Inventing Pedagogies for Professional Writing”, Byron Hawk, through posthumanist theory, discusses the concept of ambience—of a relationality from emergence that attunes to environment. He explains “This view sees cognition, thinking, and invention as being beyond the autonomous, conscious, willing subject. A writer is not merely in a situation but is a part of it and is constituted by it. A human body, a text, or an act is the product not simply of foregrounded thought but of complex developments in the ambient environment” (378). In a rectangular frame of text, even reference and contradiction as integral to argument or as footnote or bibliography entry are limited through construction as lines in the “temporal” present that allude to something beyond that they cannot call upon. I question the affordances of constructing texts as spatially minded (acknowledging that all texts are spatial in consideration of layout); what can the form of texts make available to historiographic work?

In this text/as this text, I will experiment with spatiality as form and as method/ology for doing historiography. My purpose is to provoke considerations in historiographic work in opening up texts as demonstrative of spatiality through cut up and juxtaposed elements of comparative rhetoric, Victor Vitanza’s Third Sophistic and Post-Philosophical Rhetorics, works of literature, sound bytes, glitched images, Twitter bots, and texts altered by various enhancing or disruptive processes of web 2.0 tools.

Mattering of Spatiality in Historiographic Research

I want to first acknowledge historiographic research that takes as matter of concern mattering—elements of ambience, environment, and spatiality that lend me space to form of work as significant. These scholars destabilize more traditional notions of historiographic work to draw attention to what is eclipsed in predispositioned views of time and space in not only the event being researched, but how the historical text of that event is constructed. In “Thinking beyond Aristotle: The Turn to How in Comparative Rhetoric” LuMing Mao describes comparative rhetoric as an inherently interdisciplinary research method, and as “committed to different ways of knowing and speaking and to different forms of inquiry, investigates across time and space communicative practices that frequently originate in noncanonical contexts and are often marginalized, forgotten, or erased altogether” (448). Citing emphasis placed and propagated by Aristotle’s work to define proper and essential subject for the art of rhetoric and on the body of proof for its demonstration, Mao illuminates the emphasis on a perpetual want to claim a set of concepts for rhetoric, despite the competing meanings that have accumulated over time. Mao attributes this emphasis to the need to claim intellectual progress, and as a result, disciplinary legitimacy as study. Instead of fixating on facts of essence, Mao suggests a shift to focus on facts of usage to develop a more informed understanding of the conditions of historicity, specificity, and incongruity.

Mao invokes Jenny Edbauer Rice’s rhetorical ecologies as a way of envisioning history that permits and frustrates the available means and models of discourse in the “shifting and moving, grafted onto and connected with other events” and lined “to the in-between en/action of events and encounters”. Rice’s rhetorical ecology reimagines rhetorical situation—kairotic moments of rhetoric— as “a framework of affective ecologies that recontextualizes rhetorics in their temporal, historical, and lived fluxes”. This new ways of seeing matters of fact can lead to the discovery of new paradigms of knowing. In comparative rhetoric, this look in between two texts is not to see the similarities and differences across them, but to see the effects of text—what has influenced and been influenced. The move is “metadiscplinary” (Haun Saussy); the purpose is not to guarantee uniqueness or coherence, but to represent “the condition of openness to new objects and new forms of inquiry” (453).

In that unbounded moment, I saw millions of delightful and terrible acts, none amazed me so much as the fact that all occupied the same point, without superposition and without transparency. What my eyes saw was simultaneous what I shall write is successive because language is successive. Something of it, though, I will capture.

Jorge Luis Borges, “The Aleph”

Similar to LuMing Mao’s disruption of temporal and spatial coherence to keep inquiry open, in “Writing the Event: The Impossible Possibility for Historiography”, Michelle Baliff discusses making history variable, questions what it means to not only acknowledge that history is contested, but to create histories to be contested. She explains that “‘normative historical thinking’ elides the radical singularity of the event by subjecting the event meaning by way of categories of knowledge that cannot—by definition—include the radical singularity of ‘what happened’” (243). According to traditional historical thinking, events are only significant if they satisfy a chronological narrative of beginning, middle, and end; they are constrained by temporality. Baliff is interested in unbinding events from temporality to explore the possibility of impossibility; instead of submitting an event to a particular state of being by making ontological claims about the event (which flatten it along a horizontal timeline), the event is instead merely foregrounded by its various appearances (244). Baliff is suggesting a view of events as singular, as exceptional, as not reducible to pre-existing dispositions of rules or norms. The event is instead arrivant, a future that cannot be foreseen (246). This shifts the future from horizontal expectations of temporality to a vertical orientation (246). The event is then always repeatable, it reappears in its possibility to arrive all the time instead of at a time. The event disrupts categorical systems of creating knowledge by forcing consideration in how to write historiography that reorients time as an event— as possibility (247). Writing becomes of chance because the destination of the event cannot be determined. Like Mao’s description of comparative texts being structured as representative of a condition of openness, Baliff describes the text of the event as hospitality; the text sets the table, but leaves an empty place setting for what will have arrived, what has not yet arrived, and for what could not be recognized as having arrived (254).

Victor Vitanza’s “Imagine A Re-Thinking of Historiographies (of Rhetorics)” also takes as matter of concern how and where texts are constructed by calling for re-thinking how histories are told. Vitanza works to dismantle the bounds of temporality through the use of theories of cinema as atemporal and anachronistic. He explains that historiography “plots out a transcendental, vertical line of negation, via a rationalization, that executes the conditions of possibility for realizing the desire for the lost object” (268). The lost object is a desire for linear narrative as model for historical events, but he proposes that film has replaced narrative because it can speed up events, stretch them in slow motion, work them into flashbacks, and most importantly cut and splice stating “Life is not about stories, about actions oriented towards an end, but about situations open in every direction. Life [is] made up of an infinity of micro-movements” (qting Jacques Ranciere) (282). Reimagining historiographies with film disrupts chrono-time into non-linear and multi-linear histories—histories tremble— by way of images over words because writing erases the present (273).

Mattering of Spatiality: Other of the Eye and Ear

If spatiality is ambience, developed from complexity, how can it be attuned to?

Roland Barthes’ Third Meaning looks at stills from film, working in this “inarticulable beyond” to articulate meaning beyond that of the obvious and the symbolic. This is difficult to do because as Barthes explains a third meaning is “a signifier without a signified” (61). Obvious meanings are evident; they seek the reader/viewer out (54). The obstuse meaning is one too many, it

“extend[s] outside culture, knowledge, information; analytically, it has something derisory about it: opening out into the infinity of language, it can come through as limited in the eyes of analytic reason; it belongs to the family of pun, buffoonery, useless expenditure. Indifferent to moral or aesthetic categories (the trivial, the futile, the false, the pastiche), it is on the side of carnival” (55). Third meaning outplays meaning because it is discontinuous, depletion, accent (61-62). The third meaning—theoretically locatable but not describable—”can be seen as the passage from language to significance and in the founding act of the filmic itself” (65).

allow that oscillation succinct demonstration—an elliptic emphasis… Roland Barthes

In “Other of the Ear”, Victor Vitanza recounts the space/time whe(re)n he experienced tinnitus—the hearing of noises when there is no outside source of sound—and labyrinthitis—a disorder of irritation and inflammation of the inner ear. He exclaims that it is “The thEAtRe (not a Club) of the Third!… Which would be the pedagogical site of the Revenge of the Object.”

Sub/Versions of History and Form

While the work of LuMing Mao and Michelle Baliff provide theoretical considerations of historiography that consider space, their construction does not. (Juxtaposed) To their concepts, I wish to model form theory/theory form with the sub/versions of histroiography of Victor Vitanza. In “‘Some More’ Notes, Toward a ‘Third Sophistic’” Victor Vitanza provides an account of Sophistic traditions in categories he describes as: Classical, Modern, and Postmodern or ParaRhetoric. According to Vitanza, Traditional or Classical Rhetoric is the art of discovering the available means of persuasion in the given case (Aristotle); “its ideal is unity, simplicity, and communicability”. Modern Rhetoric is the art of accounting for the available means of identification in the given case; the ideal is not persuasion but consubstantiality or sympathetic understanding (Burke). Modern Rhetoric attempts to foster heterogeneity of points of view, but semiotically attempts to “account for” a finite set of ways through which human beings are persuaded. Postmodern or ParaRhetoric, his concept of a Third Sophistic, is an art of “resisting and disrupting” the available means (that is, the cultural codes) that allow for persuasion and identification” (133). Through a pathos of distance, ParaRhetoric plays and engages ideas not just “contra to” but “along side” (133). He explains that a “Third Sophistic Rhetoric is interested in perpetual decodification and deterritorialization”; it has no faith in the game (or gain) of knowledge or the grand narrative of emancipation in history (133). Vitanza deploys these figures to consider and disrupt the role of negation and subjectivity in “the” history of rhetoric. Vitanza seeks a movement from (negative) possibilities and probabilities to (denegated) incompossibilities (counter-factual, co-extensive possibilities). The “Third Sophistic Rhetoric” as well as the “excluded middle” serve as the structure for doing hysteriography—his stance on historical work deviating from a singular construction of history. He explains “The notion of a “Third Sophistic,” as I espouse it here, can be more accurately understood according to the topoi of “antecedent and consequent” rather than “cause and effect,” and according to radical “parataxis” rather than “hypotaxis””. Vitanza limits the First and Second Sophistic to the counting of one and two in that they could only account for positions of first cause, and then cause and effect. The Third Sophistic counts to many because it is interested in the chora of hysteriography—the (competeing) voices of many.

The Third Sophistic is a view that is “post-structuralist” and “postmodern” in that it acknowledges an incredulity toward “covering-law models” or “grand (causal) narratives” of history (writing/ speaking), such as an Hegelian or Marxist dialectical view of history as leading to ethical and political “emancipation,” or to a resolution of the “unhappy consciousness.” It is a view of history (writing/speaking), instead, that dis/engages in “just-drifting.” Whereas the First and Second Sophistics are told metonymically as cause and effect, Vitanza states that the Third will be told metonymically as contingency; he states It is “effective” in that it “differs from traditional history in being without constants”; it is “‘effective’ to the degree that it introduces discontinuity into our very being”; it is ” ‘effective’ history [in that] it will not permit itself to be transported by a voiceless obstinacy toward a millenial ending” (119 qting Michel Foucault).

The “voiceless obstinacy” is what Vitanza takes issue with when argument is the basis of production—what matters— in rhetoric. He explains that too often an argument is perpetuated based on its repetition, not on its semantic content (133). He describes that an emphasis on reason as method is detrimental to what is possible. He explains that what is wanted is dissensus or hetreologia/paralogia saying ”It is Humanism that I am against. The basic, insidious assumption of Humanism is that human beings are free to deliberate on public issues, that they “express” this freedom in and when achieving “consensus” (homologia, argumentation)” (130). Argumentation is the struggle against the realization that language is the result of purely rhetorical tricks and devices, or that language is rhetoric. Argumentation, after long use, seems “solid, canonical, and binding to a nation” (131). Argument can become a hindrance to progress because commonplaces ways of fostering, protecting, and maintaining only the status quo.

Instead of negation in production, Vitanza is provoking the idea of the contingent in production: “That’s just it: feeling that the impossible is possible. That the necessary is contingent. That linkage must be made, but that there won’t be anything upon which to link. The ‘and’ with nothing to grab onto. Hence, not just the contingency of the how of linking, but the vertigo of the last phrase” (qting Jean-Francois Lyotard 134).

…the results are often startling and effective… Marshall McLuhan

In “Critical Sub/Versions of the History of Philosophical Rhetoric”, Victor Vitanza plays with the idea of contingency and vertigo as a spatial condition of reading ParaRhetoric. He calls for a change in style in discourse—not argumentation but poetics of rhetoric. He opens with a quote from Michel Foucault, “I have a dream of an intellectual who destroys evidences and universalities, who locates and points out in the inertias and constraints of the present the weak points, the openings, the lines of stress; who constantly displaces himself, not knowing exactly where he’ll be or what he’ll think tomorrow…” Michel Foucault “The History of Sexuality: Interview”.

To Vitanza, this quote demonstrates an Anti-Platonic history that pushes views of history that are considered received to the limits of the carnivalesque which oppose the idea of history as recognition or reminiscence by stylistically sub/version; that systematically dissociates identity or a single stable self which opposes history as continuity or representative of tradition by practicing an expressive, literary rhetoric like the sophists who practiced dissoi logoi (new histories of rhetoric will practice dissoi paralogoi); and that all knowledge rests upon injustice, which opposes history as knowledge by moving from representative anecdotes to “mis/representative antidotes” to be “curative fiction” (not as opposed to nonfiction, but as constructing interpretive-fictions) (54). This is a Post-Philosophical Rhetoric, a Sub/Versive Rhetoric that need not borrow the methods or contents of history. Sub/Versive Rhetoric is not attempting to convince readers but provoke an alternative predisposition (44). Like Vitanza’s careful/playful conceptual work in developing the Third Sophistic, he explains that this Post-Philosophical Rhetoric distances itself from persuasion and identification (the domain of old and new rhetoric). Sub/Versive Rhetoric is paralogism; its vision is not consensus but the searching out of instabilities as a practice of paralogisms to undermine from within the very framework in which the “normal science” has been conducted (52). Sub/Versive histories of Rhetoric are pro/claim themselves through intertextuality (53) that ispluralistic and anarachsitic and through dismemberment or creative undoing (from Mikhail Bakhtin) that uses “use of montage and quotation so one text is laced through with other texts scissor-like rhetorical figures as catchphrases, ironies, ellipses, metalepsis, aporias, parapraxis, parentheses, stylistic infelicities to destroy the Aristotelian order of propriety” (57).

Form A directs sound channels—Continuous operation in such convenient Life Form B—Final Switching off of tape cuts “oxygen” Life Forms B by cutting off machine will produce cut-up of human form determined by the switching chosen—Totally alien “music” need not survive in any “emotion” due to the “oxygen” rendered down to a form of music—Intervention directing all movement what will be the end product?—Reciprocation detestable to us for how could we become part of the array?—Could this metal impression follow to present language learning?—Talking and listening machine led and replaced—

William S. Burroughs, “Two Tape Recorder Mutations”, Nova Express

Byzantine Art: Perceptions of Dimension

The most notable aesthetic feature of byzantine art was its “abstract” or anti-natural character, in contrast to classical art’s attempt to create representations that mimicked reality as closely as possible.

When we read, our first instinct is to ask what the text is about, to determine our understanding of it. What would it mean to claim the form of texts as Byzantine art?

In Edmund Abbott’s novel Flatland describes a two-dimensional world occupied by geometric figures. One of the figures, Square, dreams about visiting the one-dimensional world, Lineland, attempting to convince the world’s monarch of a second dimension. Square is then visited by a three-dimensional sphere, which he cannot be convinced of until he sees Spaceland. Each millenium, Sphere visits Flatland to introduce a new being to the idea of a third dimension in hopes of educating the population of Flatland to its existence. Once Square sees Spaceland and his mind is opened to new dimensions, he tries to convince Sphere of the possibility of the existence of a fourth, fifth, and sixth spatial dimension, but Sphere returns Square to Flatland perturbed. Square has another dream in which Sphere visits him once again, this time to introduce him to Pointland wherein the Point (sole inhabitant, monarch and universe) perceives any communication as originating in its own mind. Sphere and Square leave Point and Pointland because of its ignorance in omniscience and omnipresence, labelling Point as incapable of being rescued from self satisfaction.

Imagine someone from our world of three-dimensions orienting themselves in a two- dimensional world—being accustomed to perception in three-dimensions but only having two available.

Katie Rose Pipkin’s presentation of her webtext “selfhood, the icon, and byzantine presence” at this year’s Bot Summit—a meeting of Tiny Subversions—of various bot makers. Rose Pipkin began her webtext/presentation with a discussion of the tenants of Byzantine Philosophy: that person is ontological rather than substance or essence; that the creation of the world is by god and the limited timescale of the universe; that the process of creation is continuous; and that the perceptible world is realization in time perceptible to mind. She transitioned from discussing iconography of saints in Byzantine murals to computer icons—both symbolic representations.

She discusses digitization using the works of Walter Benjamin thus contrasting mechanization with digitization explaining “ digitization is not mechanization, and duplication within this space is not autonomy”. Mechanically produced objects begin as identical in their construction and are placed in the world as unique entities of individual existence. Digital objects appear in multiplicity at once and forever and are not individually manipulatable. In this space, a copy is not a manipulation, as in a mechanical reproduction, it is a recreation; “like mitosis, a copy has the capacity for individual mutation but does not intrinsically affect its parent. a retweet of information is not a duplication nor a shift in scale; a retweet impacts the structural bridge of a networked idea, not the intrinsic idea itself.” Recreations in digital space exist both inside and outside of accumulated time.

Making In Spatiality: Invention by Bot and in the Margin

Twitter bots are Twitter accounts that compose tweets based on computer algorithms that generate content from mining other text sources. The results can vary from comedic to poetic as bots create new text from anything from Craigslist advertisements to museum catalogues. The tweets work in the space of juxtaposition and the form of the tweet (140 characters and an image). The form of the spliced tweet makes space for invention.

Jim Brown has a project called Making Machines that he describes as “an attempt to create new machines for the digital rhetorician” as a new form of machine for generating and interpreting arguments that the rhetorical tradition offers. Brown has created a Twitter bot that chooses at random two works from Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg’s anthology The Rhetorical Tradition which he then has to create a mashup text of. The mashup texts take the two texts to create a concept in a 3,000 word essay that is accompanied by a digital object that makes use of that concept.

The Twitter bot creates a new space for reading, a new perception that works in the abstraction of materials in spatial relations to one another.

In R. Eno’s edition of the Analects of Confucius, Eno remarks that “scholars generally see the text as having been brought together over the course of two to three centuries, and believe little if any of it can be viewed as a reliable record of Confucius’s own words, or even of his individual views”. Instead he draws analogy to the biblical Gospels as offering “an evolving record of the image of Confucius and his ideas through from the changing standpoints of various branches of the school of thought he founded”. Further, due to the materiality of the original texts—ink drawn characters on strips of bamboo that were tied together with string— “all of the books bear the traces of rearrangements and later insertions, to a degree that makes it difficult to see any common thematic threads at all”.

Eno’s edition also includes a number of appendices that call attention to the speculation of reconstructive and translation work. Eno explains the numbering of the books in the as “speculative because we don’t know the original order of the bamboo slips; moreover some slips are clearly missing, many sections are fragmentary and difficult to reconstruct. In some cases, a passage number stands by a single orphan character, signifying that we can infer that a passage including the character existed, but it is otherwise lost (there may be other lost passages for which no remnant characters survive)”. Eno’s edition of Analects, in its design/layout, draws attention to how difficult reading is and just how much need be done to/with the text so that it can be read. This edition seems to demonstrate some of the critical considerations we have discussed in doing historiographic research—making the processing of the text more visible to the reader to consider and engage with.

Imagine marginal space that isn’t marginal, but can provide space for choral construction.

The first Octalog (1988) was a panel of eight historians of rhetoric—James Berlin, Robert Connors, Sharon Crowley, Richard Enos, Victor Vitanza, Susan Jarratt, Nan Johnson, Jan Swearingen and James Murphy— who held differing positions on the nature, purpose, and methods of doing research in the history of rhetoric, the nature of interpretation, and issues concerning the belief in objective knowing (Richard Enos, Octalog II). The scholars had no agreed upon field or base for debating historical work, with matters of concern ranging from the questioning of the agnostic patterns in rhetorical argument and dialectical exchange as an inscription of gender and the implication on literacy and rhetoric (Jan Swearingen), the necessity of openness and attention toward new sources of evidence and methodologies for analysis for a more sensitive understanding of the history of rhetoric instead of one rooted in conformity and tradition (Richard Enos), to proposing an alternative position of redefinition contrary to the primary historiographical trope of rediscovery and possession of forgotten treasures in doing historical work (Susan Jarratt). The goal was not consensus, but the space of allowing ideas to interact, contradict, and leave pregnant pause for further discussion. In reading the linear transcript of that exchange, imagine someone from a world of three-dimensions orienting themselves in a two- dimensional world—being accustomed to perception in three-dimensions but only having two available.

Forming Historiographic Texts as Weak Theory

How did you read this text? Was it something taken in holistically? Or taken in as parts—some emphasized and others overlooked or overshadowed. The spatial construction of this text is demonstrative of historiographic work in that it is not bound or concrete. What I hope to have demonstrated in this spatial text of associations is that it can be taken apart. Some elements of this may be taken and reworked, while others may be left to become detrius. Kathleen Stewart’s “Weak Theory” builds from the weak theory concept of Eve Sedgwick, which she describes as “theory that comes unstuck from its own line of thought to follow the objects it encounters, or becomes undone by its attention to things that just don’t add up but take on a life of their own as problems for thought” (72). Stewart draws attention to the cultural poesis of forms of living whose “objects are textures and rhythms, trajectories, and modes of attunement, attachment, and composition” (71). The point is not to cast value to these objects or somehow get their representation right, but to wonder what potential modes of “knowing, relating, and attending to things” are present in them and their relations to other objects (71). Poesis is a mode of production through which something throws itself together; Stewart explains poesis as an opening onto something that “maps a thicket of connections between vague yet forceful and affecting elements” (72). There is something waiting to become something in disparate objects, people, circulations, publics because “a moment of poesis is a mode of production in an unfinished world” (77). Historiographic work is meant to be weak, to break, to be combined with other world elements as it is (un)formed.

Chora

Abbott, Edmund. Flatland. Seeley & Company, 1917.

Baliff, Michelle. “Writing the Event: The Impossible Possibility for Historiography”. Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 44 (3) 243-255.

Barthes, Roland. “The Third Meaning: Research notes on some Eisenstein Stills”. Camera Lucida. Hill & Wang, 1980.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter. Duke University Press, 2010.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “The Aleph”. Collected Fictions. Penguin Groups, 1998.

Burroughs, William S. Nova Express. Grove Press, 1964.

Eno, R. Analects of Confucius. An Online Teaching Translation. Version 2.1.

Hawk, Byron. “Toward a Post-Techne Or, Inventing Pedagogies for Professional Writing”. Technical Communication Quarterly. 13 (4) 371-392.

@makingmachine Brown, Jim. https://twitter.com/makingmachines

Mao, LuMing. “Thinking Beyond Aristotle: The Turn to How in Comparative Rhetoric”. PMLA.

McLuhan, Marshall. The Medium is the Massage.

Octalog. “The Politics of Historiography”. Rhetoric Review. 7 (1) 5-49.

Pipkin, Katie Rose. “selfhood, the icon, and byzantine presence”. ifyoulived.org/bot

@Rhetbot Brooke, Collin. https://twitter.com/Rhetbot

Stewart, Kathleen. “Weak Theory in an Unfinished World”. Journal of Folklore Research. 45 (1) 71-82.

Vitanza, Victor. “Critical Sub/Versions of the History of Philosophical Rhetoric”. Rhetoric Review. 6 (1), 41-66.

Vitanza, Victor “Imagine A Re-Thinking of Historiographies (of Rhetorics)”. Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 44 (3), 271-286.

Vitanza, Victor. “Other of the Ear”. http://tracearchive.ntu.ac.uk/frame5/sophist/eartrace/index.html

Vitanza, Victor. “‘Some More’ Notes, Toward a Third Sophistic’”. Argumentation (5) 117-139.